Career progression for officers in the old United States Navy used to be very different from what we know today. Officers had just four ranks open to them, midshipman, lieutenant, master commandant and captain. Congress was not open to creating more because ranks like “admiral” were a European tradition and the American republic wanted to distinguish itself from Europe.

Today’s naval officers have four levels of admiral to strive for, but it wasn’t until the Civil War that Congress gave them any chance of achieving just one admiral’s rank. Until then, achievement in the U.S. Navy was a mishmash of titles, commands and appointments. The Civil War changed that, and a long-serving naval hero would be the first to wear the rank.

The list of pre-Civil War U.S. Navy legends is a long one. John Paul Jones, Stephen Decatur, Matthew C. Perry, and Isaac Hull all achieved the highest rank possible of a U.S. Navy officer, but none were called admiral. This fact understandably annoyed many naval officers in the early days of the Navy because many became captains early in their careers.

With only four ranks available to them, the highest achievement anyone could reach was the honorific title of commodore. “Commodore” was bestowed upon officers who commanded a squadron, fleet, or any other group of ships. This fact also annoyed senior naval officers, who realized that a midshipman in command of gun boats could be called “commodore.”

While “commodore” wasn’t really a higher rank, officers who earned the title kept referring to themselves as commodore, even when their command ended. Despite the confusion and enmity it caused in the ranks, that’s just how it went from the American Revolution to just before the start of the Civil War.

In 1857, Congress finally created a flag officer’s rank, uncreatively called “flag officer.” Flag officers were little different from the Navy’s old commodores when it came down to it, however, and the rank didn’t last long. In 1862, flag officers were gone and “commodore” became an official rank.

Then came Commodore David G. Farragut.

Farragut was practically a sailor from birth. He was certainly a sailor until his death. His father came to the British colonies that would one day become the United States in 1766 from Spain. When they declared independence, George Farragut joined the South Carolina Navy. After the war was won, he moved his family to Tennessee, where his son David was born.

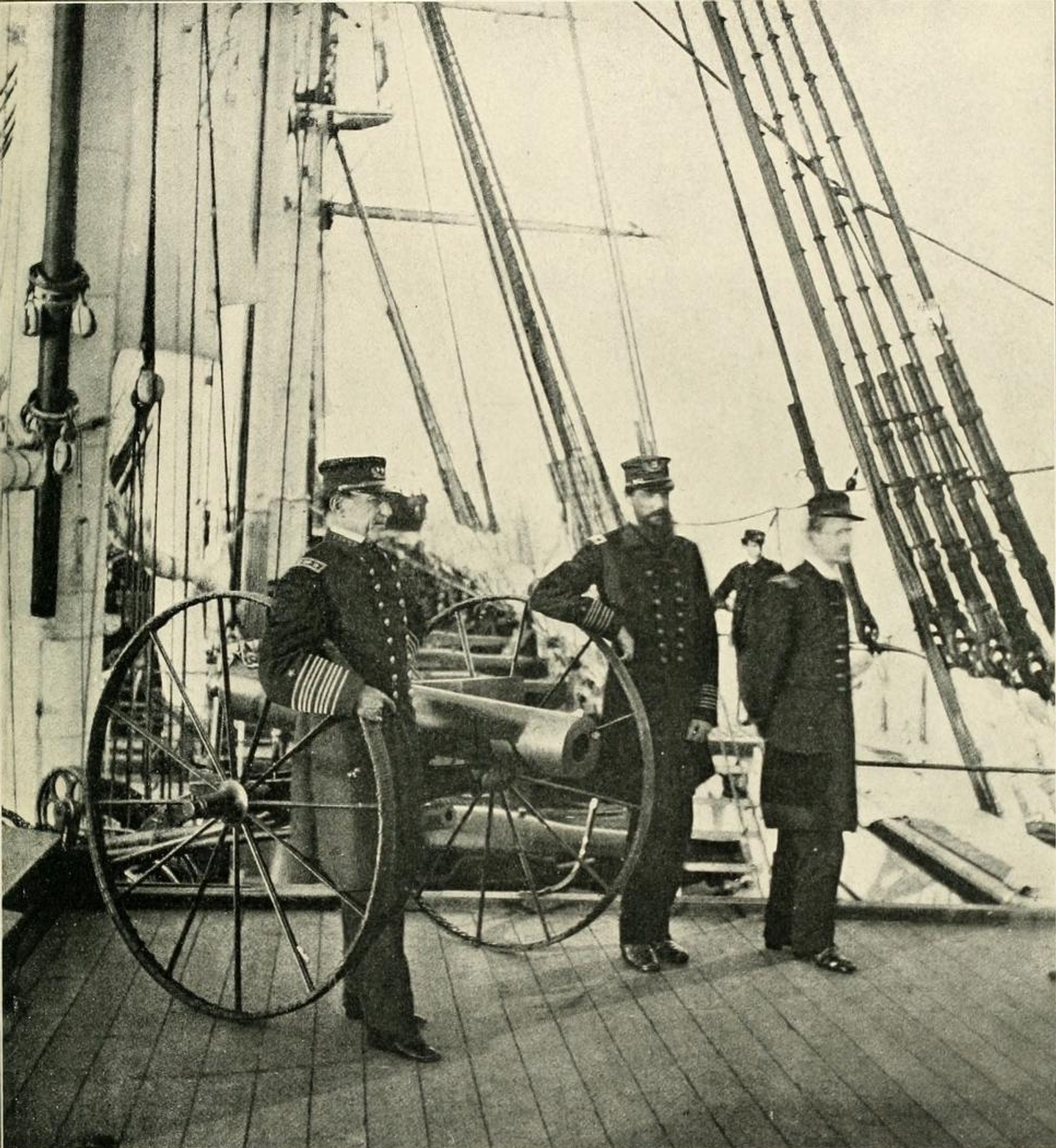

David Farragut joined the Navy at age nine and would spend most of the rest of his life at sea. He cut his teeth in combat during the War of 1812, fought pirates in the Caribbean, and served in the Mexican-American War. By the time the Civil War broke out, he was a 64-year-old Commodore given the command of the Gulf Blockading Squadron.

Three months into this command, he led the Union assault on New Orleans, sailed up the Mississippi Rivers and, along with the Union Army of the Gulf, captured the remaining Confederate strongholds on the Mississippi River. Those victories cut the Confederate States in two, the Union’s primary strategy against the south.

To honor the lifelong sailor and his recent string of wins, Congress created the rank of Rear Admiral on July 16, 1862. Farragut became the first Admiral in the U.S. Navy, and 13 other officers were promoted with him. In August 1864, Adm. Farragut and the Union Navy would capture Mobile Bay, the south’s last major port. The Confederacy was cut off from the rest of the world.

Combined with Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s capture of Atlanta, Farragut’s attack on Mobile Bay secured a second term for President Abraham Lincoln and the successful conclusion of the Civil War for the Union.