While visiting his family in Germany before World War II, William Sebold was approached by an operative of the Abwehr, Hitler’s secret intelligence service. Sebold was an American immigrant from Germany and was living in the United States. The Abwehr wanted him to spy on American military operations for the Third Reich.

Sebold agreed, but only because the spy agency threatened to harm his family still living in Germany. But the American wasn’t a pushover. Before leaving for the U.S., he visited the American Consulate in Cologne and told them of the German plot.

The Americans signed Sebold on as a double agent, and he would bring down the largest foreign espionage operation to ever operate on American soil that ended with the convictions of the spies.

William Sebold was not born a spy. He fought in World War I in the German Army as an engineer and later emigrated to the United States. There, he became an aircraft engineer and an American citizen. He only returned to Germany to visit his mother.

Upon his arrival, he was approached by a member of the Gestapo, who told him that an intelligence operative would soon contact him with a special mission for Germany. When that man finally contacted Sebold, he was introduced as “Dr. Ritter,” and told Sebold he worked for the Abwehr.

Sebold would return to the United States as Harry Sawyer with the codename of “Tramp.” German intelligence sent him to a seven-week training course, where he learned to use a shortwave radio, German codes, and spycraft. He was then told who to connect with back in the U.S. and how to send messages between those operatives and German intelligence.

Almost as soon as he was free of his German handlers in Europe, he turned right around and told the American Consul General of the German plot and that he wanted to aid the FBI in bringing it down. The double cross began on February 8, 1940, long before America entered World War II.

When Sebold returned he and the FBI set up shop for Harry Sawyer in a Time Square office in New York City. Sebold posed as a diesel engineer and the office became a safe house and meeting place for Germany’s stateside spies. His first contact, however, was with Fritz Duquesne, the ringleader of the spies.

Duquesne was a former journalist and lecturer who obtained aircraft blueprints for the German Army and planned sabotage operations at U.S. factories. Eventually, dozens of German spies passed their information, photos and blueprints to the Gestapo through Sebold/Sawyer’s New York office. They even received payment for their services through him.

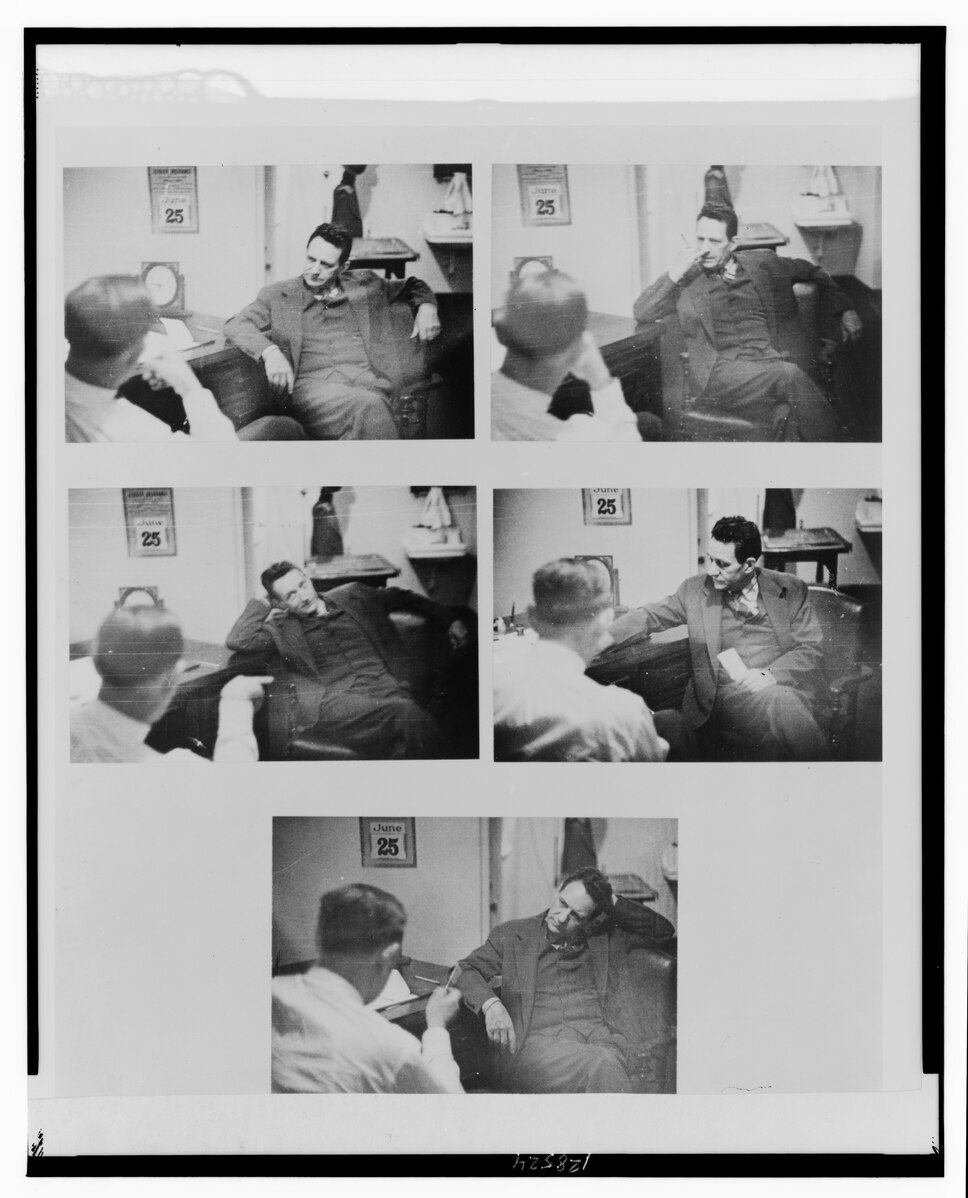

What they didn’t know was they were being recorded on audio and film the entire time, through the use of FBI listening devices and a two-way mirror planted in the office’s main room. For 16 months, the FBI maintained and monitored the transmissions of the shortwave radio provided to Sebold by the Germans. While they fed useless information back to Germany, they received information on German operations and operatives in the Western Hemisphere.

By June 1941, the FBI was ready to move in on the spy ring. They arrested 33 agents, including Duquesne. Nineteen of the accused spies pleaded guilty to the charges. The other 14 took their chances in court, but were all found guilty.

Sebold disappeared after the trials ended, presumably a part of an early form of witness protection. When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the Germans had no reliable intelligence network inside the U.S.