Following their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the entry of America into WWII, the Japanese began to implement unconventional weapons in combat. During the Philippines campaign in March 1942, the Japanese planned to release roughly 150 million fleas carrying plague to root out the American defenders. However, the surrender at Bataan preempted their use. By the end of the war, the Japanese were itching to use their biological weapons.

Developed by the infamous Unit 731 in Japanese-occupied China, a stockpile of plague was weaponized and ready to be deployed. To deliver the disease, the Japanese developed the Uji bomb. The bomb was incredibly simple and made of a ceramic container filled with corn and plague-infected fleas. A few hundred feet over the ground, a small charge would shatter the ceramic container and shower the ground below with corn and fleas. The corn would attract local rat populations and the fleas would then mount the rats who would spread the disease throughout the target area. Unit 731 tested the Uji bomb in Manchuria to devastating effect. In some cases, entire villages were wiped out by the plague. The leader of the Unit 731, Surgeon General Shirō Ishii, was especially keen to field the weapon.

During the Battle of Iwo Jima in early 1945, the Japanese planned another plague attack against the Americans. Two gliders would be towed from mainland Japan to an airfield in the Pingfang District of China. There, they would be equipped with their Uji bombs, towed over the island, and released to deliver the pathogen over the invasion forces. However, the gliders never made it to China and the pathogen was not released.

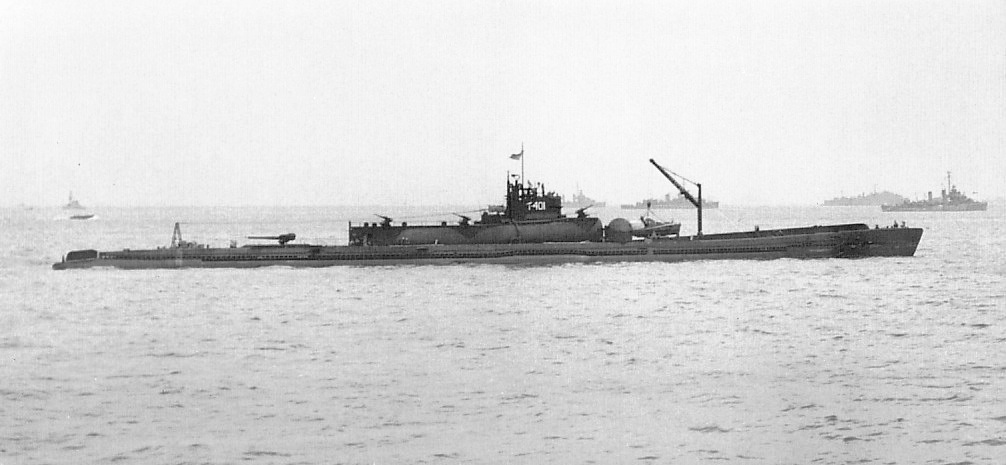

Instead, Ishii devised a long-distance strike on San Diego, California. Using five of Japan’s new long-range aircraft carrier submarines, the I-400-class, planes would be launched off the California coast to drop Uji bombs on the city. The plan was finalized on March 26, 1945. “I was told directly by Shiro Ishii of the kamikaze mission ‘Cherry Blossoms at Night’, which was named by Ishii himself,” recalled Ishio Kobata, one of the pilots selected for the mission. “I was a leader of a squad of seventeen. I understood that the mission was to spread contaminated fleas in the enemy’s base and contaminate them with plague.”

Like most Japanese operations in 1945, Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night was a one-way suicide mission for both the pilots and submariners involved. The operation was scheduled to begin on September 22 following the completion of the necessary I-400-class submarines. Though the plan was approved, Chief of the Army General Staff Yoshijirō Umezu vetoed it for logistical reasons. However, he re-approved the plan in early August 1945 when he saw that the submarine construction was on schedule. It was only the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the subsequent Japanese surrender on August 15 that canceled Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night.

By the time the Japanese surrendered, three of the I-400-class submarines had already been built with at least two more to be completed by September 2. Arata Mizoguchi, a navy commander in Unit 731, believed that Cherry Blossoms at Night would have launched if the war had gone on. If the plan had been successful, the resulting epidemic would have been catastrophic.