Gen. Ulysses S. Grant faced a quandary in his Overland Campaign driving towards Richmond. Confederate forces under Gen. Robert E. Lee were dug into what seemed like an invulnerable network of trenchworks and rifle pits near Spotsylvania Courthouse, Virginia. Several initial attacks had been bloodily repulsed, and even the weakest point of the Confederate line, a bulge around Laurel Hill known as the Muleshoe, seemed like an impossible nut to crack.

Grant, seeing that an assault on the Muleshoe was his best bet despite its formidable fortifications, decided try the unorthodox suggestion of Col. Emory Upton, a brash young officer who had distinguished himself earlier in the war. Standard infantry tactics of the day had long lines of infantry attacking in a wave, with reserves to exploit whatever breach happened in the enemy line.

Upton instead arranged his 12 regiments, composed of roughly 5,000 men, in one long tight column of only four ranks, with three regiments to a rank. They would charge at full speed toward the west side of the Muleshoe, without stopping to reload or help the wounded until they breached the Confederate fortifications. They would essentially function as a human battering ram.

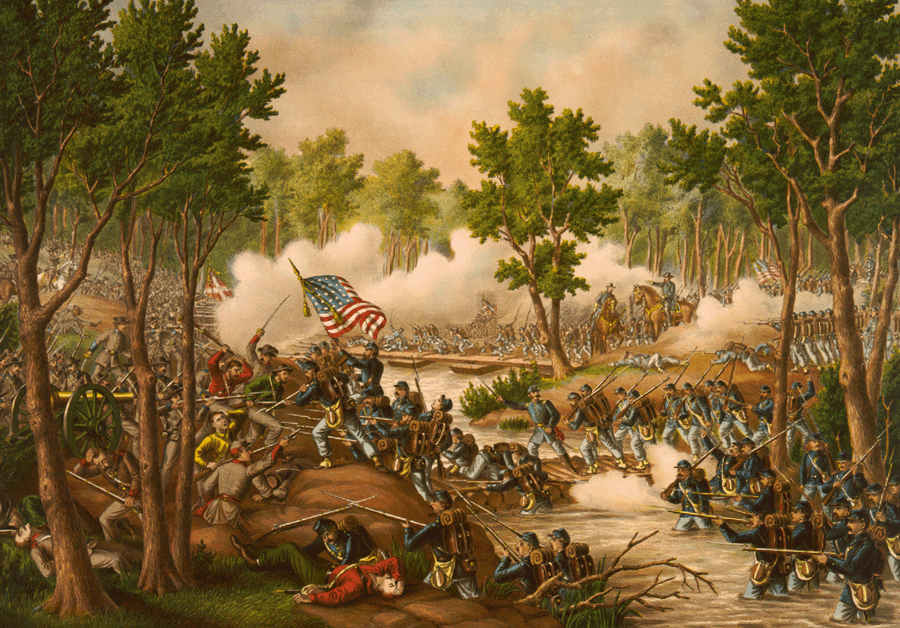

Just after 6 p.m. on May 10, 1864, the plan went forward. With a wild yell, the column sprung from its concealment in the woods and charged over 200 yards across open ground. The enemy rifle pits studding the fortifications only had time to get off a few volleys before the Union column breached their earthworks, and they even overran the half-built second line 75 yards behind the first. Lack of coordination with supporting Union units to exploit the breach and a ferocious Confederate counterattack forced Upton to retreat, but the attack had netted over a thousand Confederate prisoners and seemed to prove that Upton’s tactics could work.

Grant was impressed with the initial success of the attack and decided to repeat Upton’s idea, but on a far grander scale and with better coordination. Over 20,000 men from Gen. Winfield Hancock’s 2nd Corps would attack the northern tip of the Muleshoe, each of his three divisions forming a similar long column to overwhelm a single point of the Confederate line.

The attack launched during a pouring rain on the dawn of the May 12. The Confederate troops guarding the northern point had heard the rumble of thousands of troops assembling the night before and were on alert, but the pouring rain prevented many of their muskets from firing and they were overwhelmed by the sheer force of the bayonet assault. More than 4,000 Confederate prisoners were taken and Hancock’s attack seemed on the verge of splitting the Confederate army in half, but a Confederate reserve division desperately thrown into the mix managed to stop the Union assault, which had become hopelessly tangled and confused in the elaborate fortifications. Lee himself came riding up to personally lead the counterattack, but his frantic troops, terrified that the famed general would be killed or captured, urged him back to the rear.

The supporting Union attack composed of 15,000 troops hit the northwest point of the salient 300 yards from Hancock’s attack, moving against where the Confederate fortifications formed an angle to support 2nd Corps. This 200-yard stretch of ground turned into a hand to hand slugfest in pouring rain and mud several feet deep in some points. Waves of troops fired point blank into each other’s faces and clubbed each other with muskets, with many wounded drowning in the mud. The ferocious fighting continued for over 20 hours long into the night. The survivors of the engagement later called the spot the ‘Bloody Angle.’

Lee had quietly begun withdrawing troops to a hasty new line in the rear, and by 3 a.m. the fighting had ended with Union soldiers too exhausted to pursue. In the abattoir of the Bloody Angle there had been over 17,000 casualties from both sides, and though there were other skirmishes in the coming days Grant eventually withdrew his battered army to the southwest to force Lee out of his fortifications, for a later battle under hopefully more favorable circumstances.

The Bloody Angle was an example of an innovative idea that had turned into a disaster when implemented on a larger scale. Attacks in long columns against heavy fortifications were too apt to get tangled up amongst enemy obstacles and their own numbers, leaving them extremely vulnerable to enemy counterattack unless supporting assaults were perfectly coordinated. Enemy defenses in depth blunted whatever initial gains could be made. Upton’s tactics, however promising, could not solve the perennial Civil War problem of the superiority of defensive firepower against the frontal assault, a problem that would loom its head again 50 years later in World War I.