In 1839, the forces of Great Britain and the British East India Company invaded Afghanistan in the first major conflict of the “Great Game” – the struggle between Great Britain and Russia for control of Asia. The British quickly defeated the opposing forces of Dost Mohammad and garrisoned the capital Kabul, as well as the major cities of Kandahar and Jalalabad. However, by mid-1841 the situation in Kabul was deteriorating. The British forces made camp in an indefensible position just outside the capital. Meanwhile, two senior British officials were murdered with no reprisal from the British forces, further emboldening the Afghans.

Unfortunately for the soldiers of the garrison, a confluence of events meant trouble for them. First, the appointment of the incompetent General Elphinstone to command the British forces in Kabul. The second was a new government in London calling for increased cost-savings from the ongoing campaign. The combination of these two events led to the fateful decision for the garrison in Kabul, along with their camp followers, to conduct a retreat to Jalalabad and then back to India to escape the rising unrest in the capital. After the first unit to travel to Jalalabad in November has been harassed and sniped throughout their journey, General Elphinstone trusted the assurances of an Afghan warlord that his column would be granted safe passage.

On 6 January 1842, Elphinstone’s column of the British 44th Regiment of Foot, three regiments of Bengal Native Infantry, British and Indian cavalry, the Bengal Horse Artillery – about 700 British and 3800 Indian soldiers – as well as 12,000 camp followers – set off on their march through the treacherous Afghan winter towards Jalalabad. Almost immediately, they began receiving harassing fire from the Ghilzai tribesmen and were ambushed and attacked repeatedly over the next several days. The weather also took a toll on the Indian soldiers and camp followers who had been recruited from the more tropical climate in India. On 9 January, after losing over 3,000 casualties and having only covered twenty five miles, General Elphinstone, along with the wives and children of the officers accepted the offer of a warlord to be taken into his custody for safety, and immediately became his hostages instead. The remainder of the force trudged on, hoping to clear the snow-choked passes and reach the safety of the garrison at Jalalabad.

By 12 January, the column had been reduced to around one hundred men, mostly infantrymen of the 44th Regiment of Foot, as well as a few remaining officers on horseback. As they tried to clear a barrier erected on the valley floor many were killed while the survivors gathered on a hillock outside the village of Gandamak to make their last stand. When offered a surrender by the Ghilzai tribesmen surrounding them a British sergeant reportedly yelled back “not bloodly likely!” and thus sealing their fate. In the ensuing chaos the British infantry fired their remaining ammunition before fighting on with bayonets. Only a handful of men survived to be taken captive.. Though some officers on horses managed to escape they were hunted down and killed as well; all except for one.

“You will see, not a soul will reach here from Kabul except one man, who will come to tell us the rest are destroyed.”

– Colonel Dennie, British Army of the Indus, Nov. 1841

At Jalalabad on 13 January, Colonel Dennie was manning the fortifications awaiting the arrival of the column from Kabul when he spotted a lone man on horseback approaching the city. Upon seeing the man he is said to have remarked “Did I not say so? Here comes the messenger.” The lone survivor of the column was Dr. William Brydon, an assistant surgeon, who straggled in exhausted and severely wounded on a horse that was also severely wounded. Dr. Brydon had survived a sword strike to the head, which had cleaved off a small portion of his skull, thanks to a copy of a magazine he had stuffed into his hat for extra warmth. His horse apparently cleared the gates of the city and promptly laid down, never to rise again. Brydon was the sole survivor of some 16,000 who started the trek a week earlier to arrive at Jalalabad.

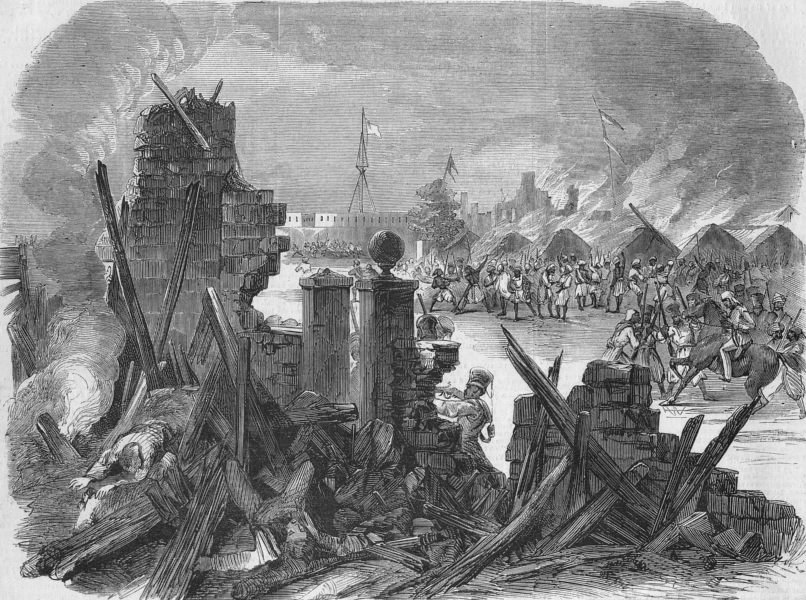

Brydon would survive his wounds and later survive another harrowing incident when we was severely wounded during the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857. General Elphinstone died in captivity. Shortly after the news of the massacre reached British officials, the decision was made to withdraw all British forces from Afghanistan, but not before retribution was sought. By the summer of 1842 the Army of Retribution had been raised and marched through Afghanistan, releasing many of the prisoners taken during the retreat from Kabul as well as exacting their vengeance before finally withdrawing on 12 October 1842.