For troops on the frontlines, receiving mail from home is a welcome reprieve from the stress and dangers of combat. During WWII, it was the job of units like the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion to make sure that mail sent from the states got to the troops overseas. What made the 6888th unique was that it was the only all-Black battalion of the Women’s Army Corps to serve overseas during the war.

Because of the high demand for frontline troops, the Army had a significant shortage of soldiers who could manage postal services in theater. In 1944, Black civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune lobbied First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt for “a role for Black women in war overseas.” Her efforts were joined by Black newspapers who called for the Army to give Black women the opportunity to support the war effort in a more direct role.

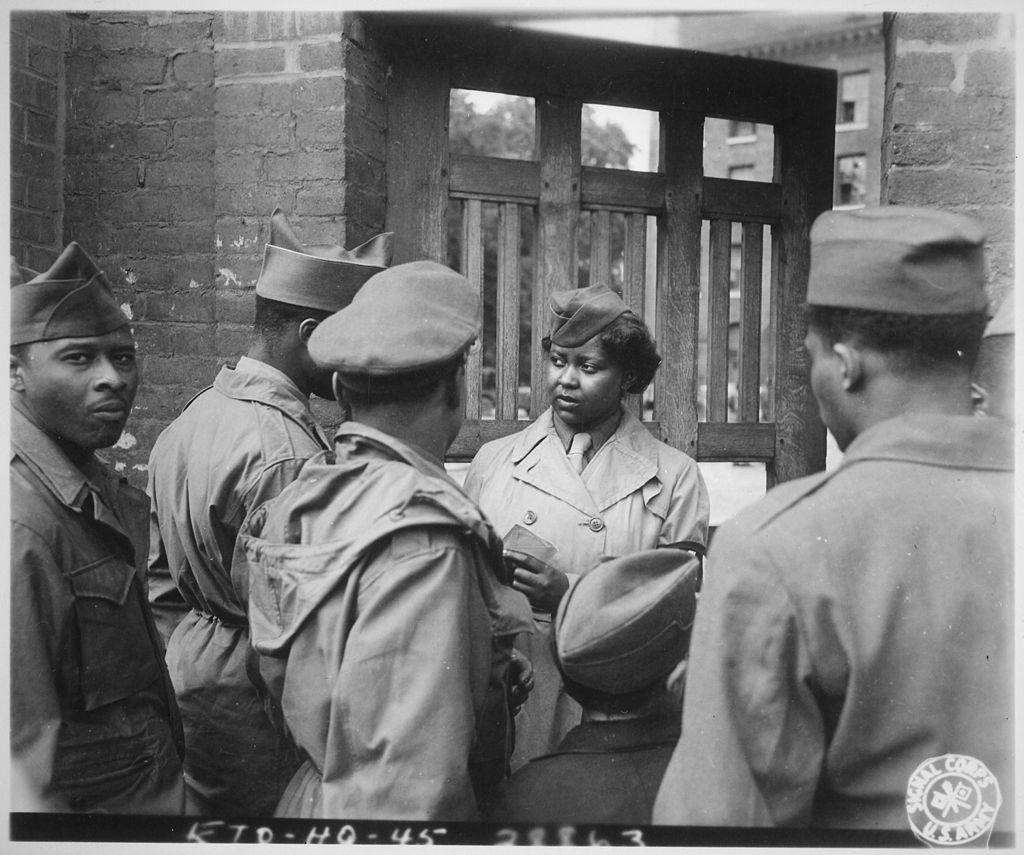

The Army responded by creating the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion in the Women’s Army Corps. Nicknamed the “Six Triple Eight”, the unit’s motto was “No mail, low morale.” The battalion was made up of 855 women, both officers and enlisted. Most of them worked as postal clerks. However, the women also filled other positions like cooks and mechanics. Because of this, the 6888th was a self-sufficient unit.

The 6888th left the United States for Europe on February 3, 1945. Twelve days later, the women arrived in Birmingham, England where they found the backlog of mail that they were responsible for. In the temporary post office, a converted aircraft hangar, mail was stacked to the ceiling. Some letters were postmarked as early as 1943. Part of the problem was that mail was commonly addressed with only a soldier’s first name or even a nickname.

The Army gave the 6888th six months to sort through the backlog of mail and sent a white officer to the unit to tell them how to do the job right. The 6888th’s commander, Major Charity Adams Earley responded by saying, “Sir, over my dead body.” The women devised their own system to sort the mail. Working in three shifts, seven days a week, each shift handled an estimated 65,000 pieces of mail. They completed their six-month tasking in just three months.

After they cleared the enormous backlog of mail in Birmingham, the women of the 6888th were sent across the Channel to France in May, 1945. The unit was camped in Rouen where they given another backlog of mail, some of which was postmarked 1942. According to Army historians, the military police of the 6888th were not allowed to carry weapons. As a result, the MPs were trained in jujitsu to deter “unwanted visitors.”

In May 1945, the women of the 6888th marched in a parade ceremony in honor of Joan of Arc through the marketplace where the saint was burned at the stake. By 1945, the women had cleared the Rouen backlog of mail and were sent to Paris. Upon their arrival, they marched through the city and were welcomed enthusiastically by the Parisians. They were even housed in a hotel where the staff treated them like top-tier guests.

With the war over on all fronts, the 6888th was cut by 300 women with 200 set to be discharged in January 1946. In February 1946, the women that remained were sent to Fort Dix, New Jersey where the unit was disbanded. There was no public recognition for the unit’s service.

In 2009, the 6888th was honored at the Women in Military Service for America Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. Seven years later, the 6888th was inducted into the U.S. Army Women’s Foundation Hall of Fame. In 2018, a monument to the women of the 6888th was erected at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. When asked about her service by the American Veterans Center, 6888th veteran Anna Mae Robertson said with a chuckle, “I was doing the best I could.”

These incredible women weren’t the only ones to break new grounds during WWII. To learn about some of our country’s first Black Marines, keep reading here.