In June 1898, Spanish soldiers on duty in Santiago, Cuba were shocked and surprised when the city began exploding around them. No one heard the crack of offshore cannons, but sure enough, there was an American ship out in the water, firing at the town.

In the dark and without warning, the high-explosive shot from the ship was a psychological victory for the Americans. Spanish soldiers in Cuba would have to be on high alert, as the United States could strike without warning.

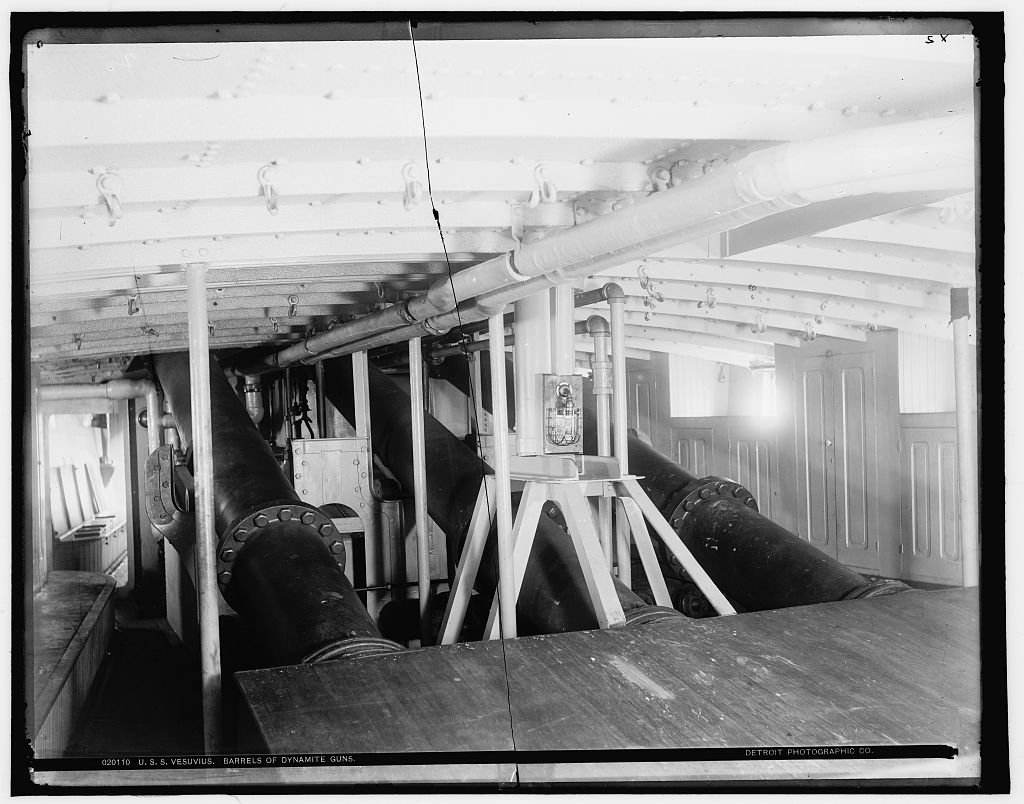

The ship offshore of Santiago that night was the USS Vesuvius. The stealthy rounds it was able to fire at the city came not from a cannon filed with gunpowder and somehow silenced, but rather it was fired by compressed air.

When we think of a compressed air gun these days, many of us probably think of airsoft players running around the woods somewhere. But at the end of the 19th century, compressed air cannons were a major technological innovation for naval warfare.

Most often known as Dynamite Cannons, the compressed air guns of the Vesuvius and other ships used multiple tanks of compressed air to fire high explosive rounds. The technological advancement was a necessity due to the new high-explosive rounds used by the Navy and elsewhere.

Early high explosive rounds were notoriously unstable. Though they could be carried aboard ships, firing one of these rounds using a traditional gunpowder charge would cause the shell to explode right as it left the muzzle of the gun. It needed a more gradual acceleration to keep the shell from exploding right away. Enter compressed air.

The compressed air not only had the advantage of not killing the gun crews and tearing a hole in the ship, it allowed for ships like Vesuvius to slip into enemy water undetected and get off a few rounds without the enemy knowing it just fired its deck guns. Another advantage was, like the Spanish soldiers in Santiago experienced, the sheer terror of being shelled from the sea without any advance warning.

On top of all that, the shells were lightweight and the compression could be reloaded aboard the ship at sea. They did have drawbacks, however. The compressed air that allowed the guns to fire off rounds without sound or the explosive death of the men who fired them meant that it had a lower muzzle velocity. As a result, the guns had to fire at a high angle which decreased their accuracy.

The Americans were also able to use field artillery with the same technology. These field guns were also used on Santiago, this time by land-based forces. Col. Theodore Roosevelt and his volunteers fielded a Sims-Dudley Dynamite Gun when capturing the city, but the future president was unimpressed, despite the improved accuracy of the field model.

Other models of Dynamite Gun could be placed on shore batteries, use steam to refill the pneumatic firing charges, or affixed to submarines. Like their seaborne cousins, the land-based models had drawbacks of their own. Some of the steam-driven cannons required 200 tons of equipment to use, fire and reload.

Improvements in the development of high explosives and high explosive rounds led to the quick demise of the Dynamite Guns and their use in land or sea combat. When the Army and Navy could go back to more traditional gunpowder charges, they did so almost immediately and compressed air guns became a footnote in history.