It was a rainy afternoon in December 1967 and war correspondent Michael Herr’s first day in country. The 27- year old Esquire correspondent found himself on the Kontum airstrip in the Republic of South Vietnam looking for a story to cover. Paratroopers of the American 173rd Airborne Brigade and soldiers of the 4th Infantry Division had recently been engaged in 33 consecutive days fighting four North Vietnamese Army regiments for control of Dak To in the Central Highlands. According to base scuttlebutt, casualties had been high but losses were particularly appalling on Hill 875.

Herr approached a recently landed CH-47 Chinook helicopter to interview returning soldiers but found only a lone rear-gunner. Noticing that the reporter was wearing no protective gear, the gunner tossed him a helmet from the back. “You keep that, we got plenty, good luck!” he said over the whir of chopper blades. Before Herr could offer his gratitude, the tandem-rotor aircraft ascended into the gray Southeast Asian sky presumably back towards Dak To.

Relieved to have acquired the protective equipment, Herr gave little thought to the “TIME IS ON MY SIDE” written in large black letters across the front and No Lie, GI in smaller letters underneath. However, Herr noticed that the sweatband inside the helmet was black, greasy and more alive now than the man who had worn it. The correspondent went cold at this grim realization and furtively discarded the dead soldier’s head gear.

American losses were indeed grave at Dak To. Official casualty estimates recorded 361 men killed and approximately 1500 injured during the month-long battle.

This brief account from Dispatches, Herr’s memoir about his war experiences, reveals more about the intensity of the combat in the Central Highlands than any official after-action reports.

If conflict interests then war fascinates – life in extremis. Perhaps this is due to the fact that the precarious boundaries between life and death can shift without warning. Good war reporting is driven by raw truth and it is no wonder that many of America’s finest writers including Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Martha Gellhorn and David Halberstam honed their craft covering one conflict or another.

Seymour Hersh was awarded the 1970 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for his coverage of the My Lai massacre that took place in March 1968. Through his diligent reporting, Hersh drew attention to the horrific slaughter of Vietnamese villagers by American soldiers in My Lai, an area thought to be sympathetic to the communist Viet Cong.

By exposing the savage conduct of Lt. William Calley’s platoon during the incident, Hersh was able to capture the vile nature of a rudderless war to a stunned American public. His accounts of the My Lai massacre galvanized those advocating for the immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops and moved hawkish Americans to reevaluate their bellicose position.

Two correspondents, however, achieved the highest distinction in this space. Ernie Pyle and Dickey Chapelle both demonstrated a fearless commitment to the craft of war reporting and made the ultimate sacrifice in doing so.

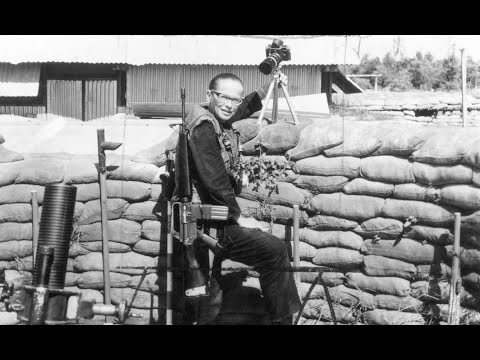

Clad in her trademark Australian bush hat and pearl earrings, Dickey Chapelle covered conflicts as a photographer from World War II, the Cold War and Vietnam. Though diminutive in height at 5 feet, the Wisconsin native stood tall among the Marines and soldiers she served alongside in dangerous places like Iwo Jima, the Dominican Republic and Vietnam.

Chapelle’s photographs appeared in Life Magazine, National Geographic as well as newspapers throughout the country.

After covering 17 U.S. led combat operations in Vietnam, she was awarded the George Polk Memorial Award from the Overseas Press Club, the organization’s highest award for bravery. In 1963, she was recognized as Photographer of the Year by the National Press Photographers Association.

She earned these distinctions as well as the respect of soldiers and Marines due to her instinctive bravery under fire.

Her motto: Only you can frighten you.

Chappelle became the only woman authorized to jump with the 101st Airborne during the Vietnam War. Even Cuban despot Fidel Castro admired her courage. Chapelle followed him during the communist overthrow of the Battista government. Castro referred to Chappelle as the ‘polite American with tiger blood in her veins.” On November 4, 1965, Chappelle was on patrol with a Marine platoon during Operation Black Ferret in Quang Tri Province, South Vietnam when she was killed by a landmine. She garnered such respect that she was buried with full Marine Corps honors.

During World War II, correspondents often experienced limited access while their work was carefully reviewed by military censors. As well, servicemen were rarely comfortable having a reporter embedded with their unit. Unless, of course, that reporter was Ernie Pyle.

The native of Dana, Indiana covered the day to day life of a foot soldier like no other war correspondent before or since. Pyle’s keen powers of observation and natural empathy appealed to readers from Broadway to Main Street.

The Scripps-Howard reporter personalized the servicemen he covered fighting in North Africa, Italy, France and the Pacific theater. Pyle made little distinction of rank, covering quartermasters and pilots with equal vigor and attention to detail. Though it was the “Goddamned Infantry” that he reserved the highest praise and made no secret of it.

Regarding the everyday hardships endured by the frontline foot soldier he said, “No matter how hard that you are working back home, you are not keeping pace with these infantrymen in Tunisia.”

In fact, certain columns irked Navy personnel who perceived Pyle’s depiction of sailors to be less flattering than the laudatory coverage of GI’s fighting in Europe.

“The Death of Captain Waskow” published in January 1944 may be his most famous column. This poignant tribute to a beloved commanding officer remains a landmark piece of literature and is an enduring testament to Pyle’s talent as a journalist.

On April 18, 1945 Pyle was killed by a sniper while covering the 77th Infantry Division on the Pacific island of Ie Shima during the Okinawa campaign.

At the time of his death, his column appeared in 400 daily and 300 weekly newspapers. Like Chapelle, Pyle earned the Pulitzer Prize for his war coverage and his advocacy for “hazardous duty pay” for infantrymen was passed into law by congress as the Ernie Pyle Bill.

Upon learning of Pyle’s passing President Harry S. Truman, a WWI veteran, reflected the gratitude of his countrymen.

“No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man,” said Truman.

Both Dickey Chappelle and Ernie Pyle share the terrible honor of falling in battle and their names are synonymous with personal courage in the field of war reporting.